“Race! The thing that bound and suffocated her. Whatever steps she took, or if she took none at all, something would be crushed. A person or the race. Clare, herself, or the race. Or, it might be, all three. Nothing, she imagined, was ever more completely sardonic.”

Nella Larsen, “Passing,” page 101

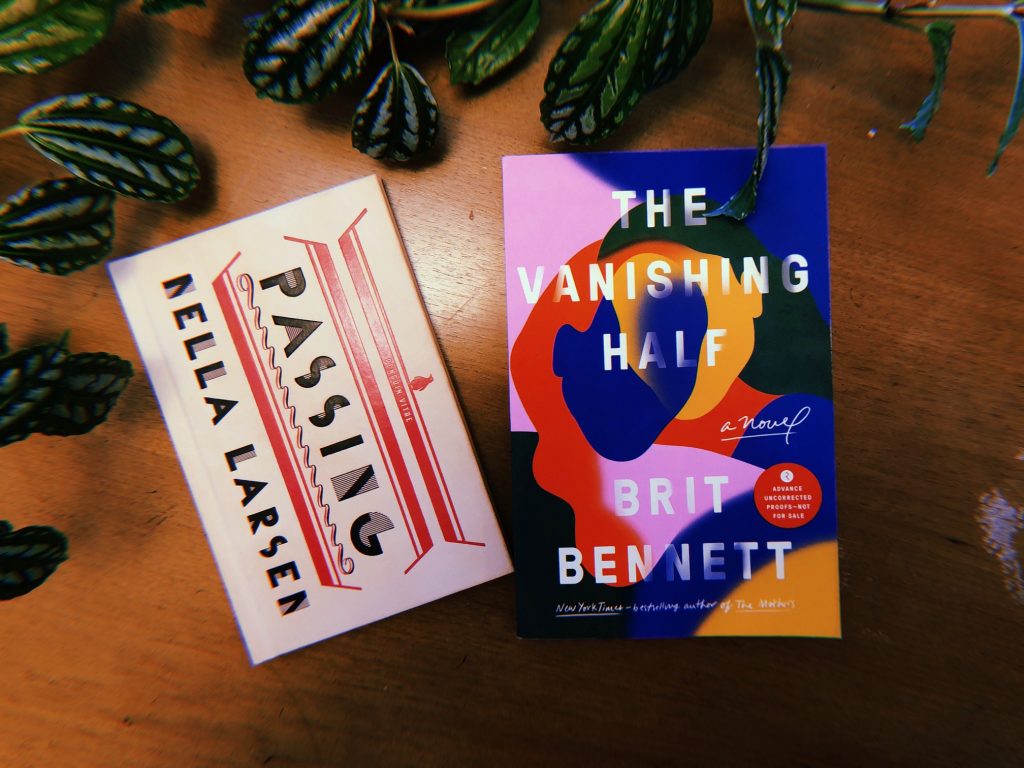

Larsen’s words here seem to represent a core theme of what so many authors dating back to the 19th century and into the 21st century wrote and continue to write about: how racism stifles, freezes, kills. Strains of this idea run through Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, Baldwin’s Another Country, and recently, through Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half. If you are unfamiliar, pick up a copy of Passing by Nella Larsen, which tells the story of two women who run into each other atop a fancy hotel after not seeing each other since their teenage years. Both of these women, Irene (protagonist) and Clare, are very light-skinned, and we find that Clare has committed to passing for white, marrying a white man and abandoning her old life. Irene is horrified by the idea, even though she also occasionally uses her light-skin privilege to do things that Black people were not permitted to do often, like dine at fancy hotels in the 1920s.

As the novel unravels, we see how these two women interact, how Clare, after reuniting with Irene, yearns to be with her “kin” again, and how Irene subsequently becomes somewhat infatuated with Clare. But ultimately, the short novel concentrates on the poison of racism—how it infiltrates, abducts, coerces, stupefies, and destroys the lives of everyone it impacts. Which is to say: everyone. When Larsen mentions at the end of the above passage, “it might be, all three,” this is it: race does not “crush” one or the other, it crushes all.

Brit Bennett’s compelling new novel, The Vanishing Half, examines the same concepts. Identical twins Desiree and Stella, years after witnessing an abhorrent instance of lynching in 1950s Louisiana that serves as the groundwork for characterizing how they will each think about race, leave the small town where they grew up to pursue bigger and better things. But this idea manifests itself in ways that could not be more disparate for each twin: Desiree marries “the darkest man she could find,” thus birthing a similarly dark-skinned daughter, and Stella disappears one day, choosing to pass for white and leave her family behind.

What Bennett does not do is chastise. Upon reading, I admit, I was hesitant that this would be the case, and we would have yet another “tragic mulatto” tale at our disposal. But Bennett, through brilliant, captivating prose is only an observer, and lets her characters become as full as they can be. We follow the twins and their children’s lives, their ups and downs, their happiest and worst days, to witness how penetrative racism is in every facet of people’s lives—no matter what your race is—while, nonetheless, building an incredibly engrossing story. She describes, through each character’s journey, how guilt, fear, trauma, and, inversely, love can make a person and inform their choices. She shows us the gravity of memory, how it is warped by time, how ideas fluctuate generationally, how some things don’t really fade or become easier. She demands that we grapple with ideas of beauty, how overt forms of discrimination based on white beauty standards weigh on public memory and representation, and how covert objectification, fetishization, and exoticization of Black women’s bodies hinder and corrupt everyone’s ideas about Black women’s worth, place, and strength.

To me, this novel was fueled by Stella and Desiree’s gripping relationships to each other, their mother, “the race,” and their hometown, but it is driven by Desiree’s daughter, Jude. Jude is the heart of this novel, and Desiree and Stella’s heart-aching relationship serves as its soul. Jude’s story acts as a counterpoint to both her mother’s and aunt’s, the guiding force that sets the story in motion. And once you reach this point in the novel, you cannot put it down. With The Vanishing Half, Bennett delivers a meditative, intense, fresh examination of Black womanhood in all its unique and diverse forms. Already I can see this text becoming a classic, to be paired well with those aforementioned titles and the ones it will surely inspire.

Coming out this Tuesday, June 2nd––you don’t want to miss this one.